Afbeelding

By Marvin Hokstam

History is a fickle thing, as it oftentimes is selective who it chooses to keep alive. Stories of certain people who deserve to be known, are often not told. Heroes thus become no more than mere footnotes in the annals if they are even mentioned at all.

We all know why.

In our history as Africans who were stolen and kidnapped overseas, we know our own heroes.

People who withstood.

People who survived so we could live.

Knowing our history is keeping them alive.

LAST MARCH my friend Otmar “Kodjo” Watson visited the Assin Manso Slavery Site, where he was impressed to see the photographs of so many great Emancipators.

He discussed the possibility then of adding a photograph of an anti-slavery rebellion leader from Suriname, where we are originally from, to the collection. Suriname is a country on the northeastern shoulder of South America; it is a former colony of the Netherlands, which shipped millions of Africans there to work as slaves on plantations. Many of them revolted. Otmar suggested to have one of these heroes added to the gallery at Assin Manso Slave River Site.

We presented Kap’ten Broos, grandfather to my late grandmother Bertha. A legend who subtly lives on in my family.

“Afo Broos, as he should be respectfully referred to, was a proud Black man who lived free when slavery was norm in Suriname.

Captain Broos was a proud Black man who was born around 1821 to Black people who had escaped slavery in Suriname. His grandmother was Ma Uwa was born on the continent of Africa. She fled the plantation where she was put to work, together with his mother, Ma Amba.

Captain Broos was a proud Black man who was born around 1821 to Black people who had escaped slavery in Suriname. His grandmother was Ma Uwa was born on the continent of Africa. She fled the plantation where she was put to work, together with his mother, Ma Amba.

They joined with other Africans and built a stronghold at Rorac, in the thick forest behind the lush Plantation Rac-a-Rac on the mighty Suriname River, not far from the country’s capital Paramaribo. From this impenetrable location Broos led a forceful band of heroes who regularly attacked the slave plantations and freed other Black people who were being kept in bondage. Broos and his people were called the “Baka Busi Nengre”, the Negroes from Behind the Forest.

Broos was tall and strong, and he had a reputation of being just, fearless and combative. He was loved by his fellow “Baka Busi Nengre” and feared by the colonials. The tales of his victories are many. Even the Redi Musu, the dreaded but loathed army of former slaves who were enlisted to catch Maroons -as they called Black people who preferred freedom in the forest above slavery-, feared him.

One story goes that the white slave masters once launched a pontoon full of these Redi Musu toward Rorac to battle against Kap’ten Broos; but upon their arrival they laid down their weapons and refused to fight, out of respect for him and daunted by his skill. The Redi Musu took off their red caps, turned their backs toward their white masters and joined Broos’ army.

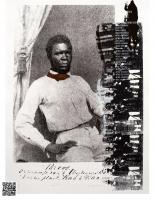

Broos is the only anti-slavery rebellion leader of whom a photograph exists. The photograph was taken in 1862, when he was invited to have an audience with the then Governor of Suriname, who pleaded with him to stop attacking the plantations. As he sits there, his face strong, proud, fearless and combative, but also just and honorable, he represents all fighters from our country who knew that Africans were not meant to be anyone’s slaves.

That we were stolen from Africa.

And that in Africa is where we belonged.

That we were always free.

That we were meant to be free.

So his life’s mission was to raid plantations and free other enslaved Black people, which he did until 1862 when he traveled to the capital of Paramaribo at the invitation of the then Governor of Suriname, who pleaded with him to please stop attacking the plantations.

That is when they took his photograph. It is the only known photograph of a Black freedom fighter who fought slavery in Suriname. There were hundreds of these heroes, but Broos is the only one whose photograph we have. As he sits there, his face strong, proud, fearless and combative, but also just and honorable, he represents all.

In 1862 he signed a peace accord with the colonizers, that gave him the rights to the Plantation Rorac and named him village elder; Kap’ten for Captain. In return for him no longer attacking the plantation, the colonizer agreed to leave him and his people in peace, on their land that they had carved out and conquered and made their dominion. It was theirs.

Rorac and Rac-a-Rac are today still owned by his descendants.

Broos and his brother Kaliko who had joined him in the fight against the oppressor, are the forefathers of countless proud, well-known Black Surinamese families.

Broos died in 1887. It is said that he was laid to rest in a secret spot on Rorac, alongside his brother Kaliko.”

The response to our presentation was swift and positive. “We are glad to accept your request to have Captain Broos’ photograph to be mounted as part of the Emancipators at the Assin Manso Slave River Site,” the manager at the Site wrote us back.

I was psyched and hype for days upon receiving their response. Imagine the feeling you have at your proudest moment and it will not come close to the sentiment that rushes through me at the thought of my legendary great-great-great grandfather going back home to this sacred place. Imagine the sense of pride that pours out of me, for being the one with the honor to take him home.

The photograph of Kap'ten Broos hangs in a museum in Amsterdam. The piece that we chose to be mounted at Assin Manso is actually a piece of art by painter Remy Jungerman, who is also a descendant of Broos. In "CAPTAIN BROOS", which he produced in 2006, he superimposed Kap'ten Broos on a silkscreen with vertically to his right a group of Maroon Kap'ten (Captains).

This piece links me to my ancestral history. I am honored that Broos will come to be mounted in ths setting in Ghana, where he will stand for Maroon leaders who did not bow to the colonial rulers. I am also honored that as artist I could be inspired from this source that has such a rich cultural history."

We came prepared with three large 70 X 90 cm pieces, beautifully printed, ready to be printed. Three, because if the first doesn't work, the second will and then we still have one more try left. The photograph has a QR code to the left bottom, that leads to a page on AFRO Magazine that we will fill with background on Broos.

We came prepared with three large 70 X 90 cm pieces, beautifully printed, ready to be printed. Three, because if the first doesn't work, the second will and then we still have one more try left. The photograph has a QR code to the left bottom, that leads to a page on AFRO Magazine that we will fill with background on Broos.

Sankofa

The first selfie I took of myself here was with this statue of the Bono Adinkra symbol Sankofa.

Sankofa is a word in the Akan Twi and Fante languages of Ghana that translates to "go back and fetch, seek and take". It is represented by a bird with its head turned backwards while its feet face forward carrying a precious egg in its mouth.

History happens constantly.

And sometimes, with a bit of effort, you can write it yourself.

With some effort you can bend it to your will.

We all know that this has happened.

So when you get the opportunity, write your own history.

That's why I'm in Ghana right now.

To write Kap'ten Broos into his place in history among other Africans who refused.

He represents

People who withstood oppression

People who survived so we could live.

Telling our history properly is keeping them alive.

Home is a place where I had never been before

So on Thursday I traveled to Ghana on this sacred mission. This trip had touched me deep in my core for so many reasons, even before I set off from Amsterdam. As turbulence was gently rocking the descending aircraft and we were being told to stow away our tray tables and turn off all electrical apparatus, I just sat there and peeked out of the window with another few hundred meters to go, and soaked in a bird’s eyes view of the continent of my forefathers before they were stolen.

The continent I had been told lies on top of lies about; lies about dominating poverty and tearslurping flies in the corners of hungry airbellied children’s eyes, lies about a continent that was supposed to be in perpetual darkness, stuck in the dark ages, poverty and the destructive warfare that was supposed to be akin to Black people; lies that many people like me still believe.

But all I could see from way up in the dark of the 8.00pm night were lights for as far as my eyes could stretch. Lights and life.

Then we touched down and I had to take off my jeans jacket because the warmth was enveloping me; welcoming me like a cozy blanket into the home I had never before been to. It’s an indescribable feeling.

Like getting first impressions about a place that you have never before been to but that you know so well. It’s as hard to explain as it is to comprehend.

“Welcome home,” said the customs supervisor who sauntered by to check if her subordinates were doing their job well. She was short and stout and her face was hidden behind a facemask, but I could see her eyes glistening naughtily as she surveyed the tall visitor that towered over her. “I like your hair,” she said approvingly.

Never before had I had a border employee utter four words with more meaning to me. I grew up in a time in a country where my kinda hair had to either be shaved or straightened; Only someone who runs the border of a country of people who look like me, will be able to say those words and give them meaning without consciously intending to.

Then her eyes smiled and she told me I was good to go.

And this was just the start. And it appears to be a modest note. Imagine the high one.

Broos Babel, also called Kapten Broos(1821-1880) was the leader of the Bakabusi Suma or ‘Brooskampers’, a group of Maroons who settled at Rorac, a camp behind the RacARac plantation on right bank of the Suriname River, around the abolition of slavery in 1863. A true anti-slavery hero, this 19th century Surinamese freedom fighter spent his life opposing oppression

The Bakabusi Suma lived in the forest far away from the plantations from which they had previously fled. Their habitat, also called Kaaimangrasi, was barely accessible to armed settlers looking for them. The first Maroons lived here as early as 1740.

They often fought against the white settlers and plantation owners. In 1760, a hundred years before the abolition of slavery, the Ndyuka had already concluded a peace treaty with the colonial government and were therefore free and independent.

The camp of Broos and his younger brother Kaliko (born in 1835) was located in the extensive swamps at the upper reaches of the Surnaukreek, a tributary of the Suriname River. Just before the abolition of slavery, the Brooskampers resisted a last attempt by the government to force them to return to the plantations. This with the aim of making the former slave owners eligible for the state compensation per slave. However, the patrol members failed in their intent and retreated to the Rac à Rac plantation. Captain Broos thus became a well-known Surinamese independence fighter.

Broos is the only Surinamese freedom fighter who has been photographed. The black-and-white photo probably dates from 1862 when Broos was in Paramaribo to conclude a peace agreement with Governor-General Van Lansberge. It is then that he received the title of Kapten from the government and was officially assigned to Rorac, a long-abandoned sugar plantation.

After the emancipation of 1 July 1863, the Brooskampers settled permanently in Rorac. Among them are Broos’ brother Kaliko, his sister Mandrijntje, his mother Ma Uwa and his grandmother Ma Amba, who was still born in Africa, in Ghana. Three families emerged from Broos’ camp, of which Babel and Landveld are the largest. However, the Deekman family contains the most direct descendants.

This page on AFRO Magazine is dedicated to his memory.

Descendants mounted the famed photograph at the Asen Mason memorial site in Ghana in 2021. In 2024 they returned to replace the black-and-white photograph with a colorized version.

Descendants also honored Broos' memory by starting a foundation in the Netherlands -The Broos Institute- that boasts of being the first educational institute in the Netherlands to offer university level schooling.